One Big Idea: M&A Branding

Mergers and acquisitions lead to a host of integration questions — including a set of important branding decisions. With many contributing factors to consider, there are four general strategies for brand architecture in these situations. In this episode, Bill looks at M&A branding strategies and details the process for determining the best path for specific scenarios. If you like our podcast, please subscribe and leave us a rating!

Podcast: Download Subscribe: iTunes | RSSTranscription

Bill Gullan: Greetings, one and all. This is Real-World Branding. I’m Bill Gullan, President of Finch Brands, a premier boutique branding agency and this is One Big Idea. If you listen to us, over the last year or so that we’ve been doing this, often these One Big Idea or focused soliloquies, if you will, have revolved around topics that are fairly elemental when it comes to brand development, things like brand architecture, how to do naming, and how to think about messaging. We’ve focused also, often, on brand creation, starting up or thinking about brands for the first time, or in a different way. This week I think we wanted to get a little bit deeper into topics that arise in fairly sophisticated branding environments, and so we’re calling this Branding M&A.

The reason for that is that oftentimes, a corporate level re-branding or major brand architecture project arises from the fact that there has been a change to the formation of the company – often through a merger or acquisition or being on the receiving end, being acquired or a strategic alliance. Often there is something happening at the ownership level that creates an obvious need to think through topics related to the brand. So we’re going to spend today, the next few minutes, talking about some strategies that companies use, and the strengths and weaknesses of these strategies, when it comes to thinking through what a brand looks like, sounds like, and means, on the heels of a merger or an acquisition.

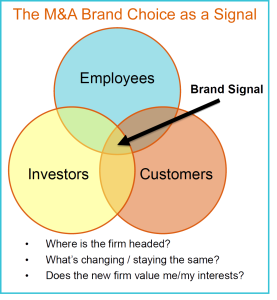

First of all, it is important to know that as you approach choices around brand strategy or brand architecture on the heels of something like that, a merger or an acquisition, there are signals that are sent based upon how these choices are managed, and what is ultimately decided. You send a signal to your customers about where the firm is headed, what’s changing, what’s staying the same, who you’re going to be working with, etc. If you’re talking about a services company, what’s the process, the prevailing way in which services are delivered?

First of all, it is important to know that as you approach choices around brand strategy or brand architecture on the heels of something like that, a merger or an acquisition, there are signals that are sent based upon how these choices are managed, and what is ultimately decided. You send a signal to your customers about where the firm is headed, what’s changing, what’s staying the same, who you’re going to be working with, etc. If you’re talking about a services company, what’s the process, the prevailing way in which services are delivered?

Based on the choices that you make in terms of the go-to-market brand after an M&A type of situation, you’re sending a signal to your existing customer base. That includes the customer base of the acquirer and also the acquired. I think in some ways it may be most important for the customer base of the acquired, because they’ve chosen specifically to work with a company that has now been acquired by a larger or a different entity, and they naturally want to know whether the reasons on which they’ve made their choices are still true and valid.

In some cases, if we’re dealing with companies in the same industry that have been competitors for a long time, you may have a customer of an acquired brand who has chosen specifically not to work with the acquirer brand at some point along the line, and thus it is very important to think about the signal that your brand architecture choice on the heels of M&A sends to the customer base of both the acquired and the acquirer.

It sends a really strong signal as well to the team, to the employee base. Again, perhaps most especially, to the team of the company that is being acquired, where often the blood, toil, tears, and sweat, as Churchill would have said. That is often misquoted, but blood, toil, tears, and sweat, have gone into building the brand and building the business, and competing, and winning, and earning the right to be thought of as an acquisition target, but now, all of a sudden, this other entity has come in, and they’ve written a check or whatever it is, and they now have dominion over decisions related to the brand. Obviously there’s a lot of cultural considerations here, but one of the signals that can be sent in a situation like that, that it’s very important to consider, is to the employee base, and also to investors and owners and other key stakeholders.

Ultimately the signal that is sent through choices around M&A is about the future vision for the company, where it’s headed, what the thesis is related to the acquisition. Again, what’s changing, what’s staying the same beyond the name or the logo, although that heralds a bit of, specifically what will or will not remain. Then ultimately the value. From a customer, an employee, an investor perspective, will this new entity value me/my interest – is it organized to serve someone like me on the basis that I’ve chosen this company in the past? Really important to think about the merger and acquisition branding strategy and choice as a signal to these key audiences.

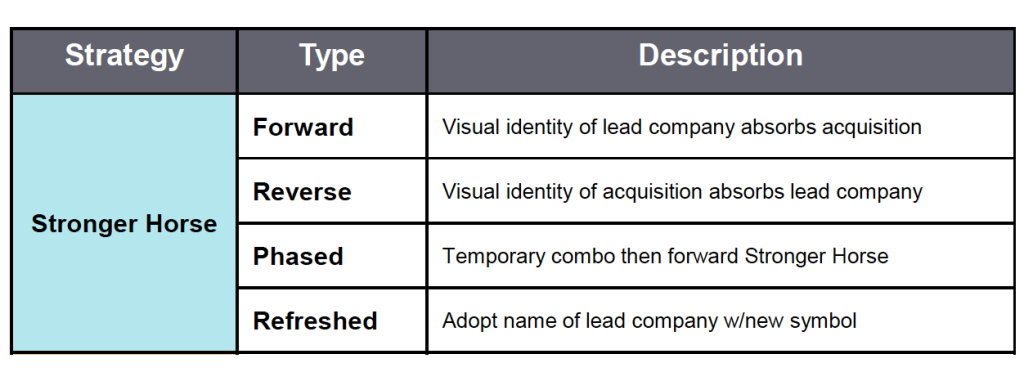

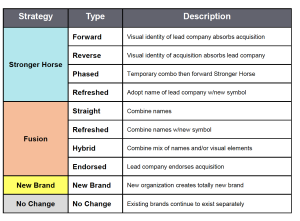

Now, when it comes to the approaches to brand architecture, I’m just quickly going to summarize the 4 different types of post M&A brand architectures. There’s a lot of depth here. There’s a lot of study around which is right for which type of situation and also what the historical financial returns have been a few years removed. There’s a lot of thinking around this, but we will focus here just on defining those 4 types of brand architecture approaches and each of these have sub-types, which we’ll go through quickly.

Now, when it comes to the approaches to brand architecture, I’m just quickly going to summarize the 4 different types of post M&A brand architectures. There’s a lot of depth here. There’s a lot of study around which is right for which type of situation and also what the historical financial returns have been a few years removed. There’s a lot of thinking around this, but we will focus here just on defining those 4 types of brand architecture approaches and each of these have sub-types, which we’ll go through quickly.

Type number one is called what we would say, the ‘Stronger Horse.’ This is where the company, often the one who was initiating the acquisition, or is the slightly larger or more dominant partner in a merger – they may not be larger, but they may have been the ones who brought the dollars to the table – the upper hand merger partner chooses to elevate one brand or the other, on whatever basis they consider one brand to be stronger. It may be size, it may be reputational qualities, but the Stronger Horse brand architecture strategy is to pick one of the brands and run with it.

Within Stronger Horse, there are 4 different sub-types of brand architecture decisions here for M&A. The ‘Stronger Horse Forward’ type is where you take the visual identity and the nomenclature of the larger or lead company in the deal, and the acquisition is absorbed and that name or logo goes away.

Another way to do this, and you don’t see this as frequently, is the ‘Reverse Stronger Horse,’ which is where the visual identity or the name of the acquired company, which often is much smaller, at least at a brand level, absorbs the lead company.

I remember when I was in Charlotte, this happened a couple of times in the banking industry. First Union, for example, had had a ton of challenges on the customer service side of the house, and thus some reputational damage, made an acquisition of Wachovia. Wachovia was a Winston-Salem based bank that was about 1/6 of the size of First Union, but the re-branding put the Wachovia name and image in the lead position, in part because they used the Reverse Stronger Horse. They considered the acquired brand, though much smaller, to be stronger – or at least also having none of that baggage and an opportunity to define itself.

The third type of Stronger Horse is the ‘Phased Stronger Horse,’ which is where you go with a temporary combination and immigration strategy that ultimately ends up with a Stronger Horse brand situation, where one name is ultimately elevated.

Then ‘Stronger Horse Refreshed,’ or the Refreshed Stronger Horse, is where you adopt the name of the lead company, but you develop a new logo, a new symbol, or a new color scheme to reflect the fact that there is some newness and some change.

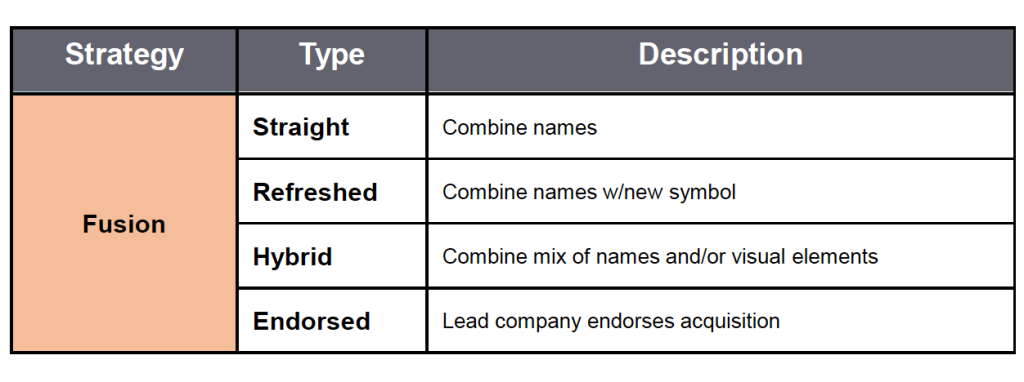

The second prevailing brand architecture type in an M&A situation is what we would call ‘Fusion.’ Fusion involves selecting some identity assets from both partners in a merger or an acquisition and integrating them into the corporate identity.

’Straight Fusion’ would be just a combination of names, and an example of this would be ExxonMobil, where Exxon acquires Mobil, and I actually don’t know who the larger partner was, but it’s a merger and the new company becomes just a mash-up. It’s ExxonMobil, so that’s a Straight Fusion.

A ‘Refreshed Fusion’ example is ConocoPhillips, we’re sticking with petroleum here, would be where the names are combined, but there’s a new graphic identity, symbol, icon, or topography, that indicates that there’s newness here, but that you still don’t want to sacrifice the equity of either of the major merger partners.

A ‘Hybrid Fusion’ might be when you combine the mix of names or visual elements. An example of this would be when Boeing acquired McDonnell Douglas, the brand identity consisted of the Boeing name, but the McDonnell Douglas logo. It really was a mash-up of brand assets, but retained elements of all merger partners here.

Then last would be ‘Endorsed Fusion,’ where the lead company endorses the acquisition in terms of brand architecture. An example of this would be when Gannett acquired CareerBuilder, CareerBuilder became careerbuilder.com, a Gannett company. These are ‘powered by’ types of brand architecture strategies within the Fusion realm. These I think are the most predominant, you see these pretty frequently. There’s 4 options within each of them.

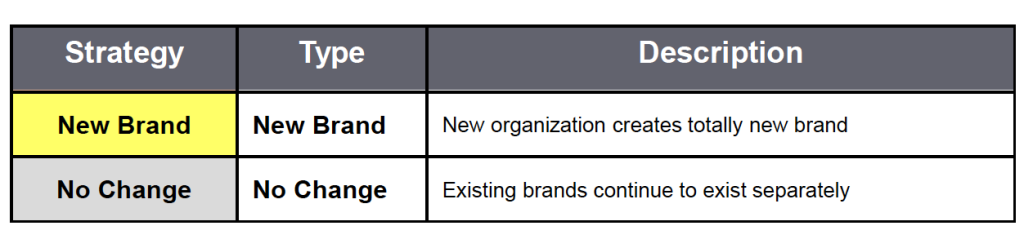

Then the third brand architecture directive is a New Brand. There’s a lot of famous ones of these. Lucid Technology, or when Bell Atlantic and GTE merged they created a new name that’s called Verizon. They could have chosen one name of the two, they could have gone Bell Atlantic-GTE and just ‘Fusionized’ it, but they wanted to communicate a shared future. They wanted all members of the team to feel valued, and they wanted to signal that there was something new and exciting happening, and certainly the telecom world was changing a lot, so Verizon is an example of a New Brand.

Then, in some cases, there is no change at all. The acquiring company leaves the brand of the acquired company alone and just collects the checks. There are reasons to do this, too. One reason is that it maintains all brand equity. Team members do not feel slighted, that signals to stakeholders a ton of continuity. The con is that how these things integrate may be unclear. There isn’t any transfer of positive equity. Synergies may be unrealized. The rationale behind the merger or the acquisition likely included some degree of efficiency, and that may not ultimately be delivered to the marketplace or to stakeholders.

We would call those scenarios, the New Brand or the No Change, the bookends. These are the extreme examples of total change or no change when it comes to brand architecture post M&A.

In summary, and we’ll stop here, even though there’s a lot that lies beneath each of these. Four predominant M&A brand architecture strategies. There’s the Stronger Horse, there’s Fusion, there’s a New Brand, or there’s No Change. The specific situation in which the right brand architecture approach is defined is absolutely situational. It is based upon category. It is based upon history. It’s based upon relative brand equity. It’s based upon go-forward plan and objective. It’s based upon the operating and growth thesis that led to the merger or the acquisition.

Oftentimes, Finch Brands is called upon to help untangle, in the case of a situation like this, what the right approach is. Often, one of the examples that we cited, unfolds over a period of time, that would be the Phased Stronger Horse.

Well there’s all sorts of migration strategies here that are middle grounds within brand architecture, and often, given the heat of the acquisition and the pace and the rhythm, and the required workflow to fully acquire an organization, and for large organizations this could take years, it makes sense to pursue a migration strategy, to select the approach here to be done for a fixed increment of time and for it to evolve into its more steady state. Blathering here a bit about philosophical concepts, but suffice it to say brand architecture is super important, it is complicated, and it’s something that we spend a lot of time on here at Finch, and it’s also very stimulating. There’s a bunch of different approaches here and, as noted, the situational differences are what ultimately carries the day in terms of what the correct approach is for the companies in question.

That’s One Big Idea. Appreciate your time. As always, we’d love some dialogue around these topics, or others that are related to the world of brand and business building. Please feel free to communicate with us via Twitter, @BillGullan or @FinchBrands. Love ideas for future guests, love comments on what we’re doing, topics you’d like to see us get into. As always we appreciate you subscribing to this podcast to make sure you don’t miss an episode. We appreciate you giving us a ranking in the App Store of your choice if we have earned it. On that note, and in that spirit, we will sign off from the Cradle of Liberty.